④ デスティネーション・マネジメントとフローベース・アプローチ

研究者と地域コンサルタントの両方の顔を持つ筆者が10年にわたる試行錯誤の中でたどり着いた、観光地の関係者間で効果的に認識の共有と意思決定を行う手法とは。

観光客の流動(フロー)に着目した手法を紹介する。

ザンクト・ガレン大学准教授

Pietro Beritelli

1 従来のデスティネーション・マネジメントの限界

世界中の国や地域、または社会が、それぞれの対象とするエリアのマネジメントとマーケティングを向上させることによって観光の価値を高めようと試みている。「デスティネーション・マネジメント」の重要性はここ40年あまりで高まってきているが、それには特に行政機関が「旅行」という多様で広く行われている現象を改善すべく努力している観光客や観光産業、地域住民を支援しようとしていることが背景としてある。その成果はしばしば、多額の費用をマーケティング・コミュニケーション、あるいは観光関連企業間の連携や総合的な地域の発展を目的とする戦略づくりに投じるようになっているDMO(Destination Marketing or Management Organizationと呼ばれる組織を通して社会に認識される。このようなDMOのこれまでの取り組みに対してはいくつかの批評的な分析がなされており、下記のようないくつかの誤解や矛盾、誤信が指摘されている(総合的な批評は Beritelli, 2019; Beritelli, Bieger, & Laesser, 2014; Beritelli & Laesser, 2019; Beritelli, Reinhold, Laesser, & Bieger, 2015; Pike & Page, 2014 を参照のこと):

●DMOは、行政の管轄によって定められた特定のエリアに対して責任を有する。しかしながら、観光客は旅行の際に、都市や地域、または国の境界で留まることはしない。

●DMOは、ターゲットとなるグループを設定した上で、意味あるマーケティング・ミックスによって彼らに働きかけなければならない。しかし、観光客はそれぞれ異なる活動を行う上、一人で旅行することは少ないため、様々な属性が混在するグループとなる。また彼らは場合によっては、友人や親戚を訪問したり、出張や社会的義務、または別荘や自己所有の船などを利用するために地域を訪れる。そのため、実際の旅行においては従来の市場セグメンテーションは有効に機能しない。

●DMOは、観光客を惹きつけ、実際に来訪してもらうことによって担当するエリアのマーケティングを行うが、大規模な観光事業やアトラクションを営んでいるわけではないためにそれができない。また、地域の観光関連企業に対して観光サービスを販売したとしても、満足のいく売上規模には到達しない。

●DMOは、観光地全体のマネジメントを行う必要があるが、地域で発生する観光に関する全ての事項を管理・調整するだけの資源や手段を有していない。

●観光地は、一般的な商品と同じように独自のプロフィールや特性を有する必要がある。しかしながら、観光客は年間を通じて地域でそれぞれ異なった活動を行う。年間あるいは長期の期間にわたる様々な事業における価値創出の可能性を高めるためには、活動の多様性や観光の種類を増やす必要がある。

上記を含めたデスティネーション・マネジメントに関する他の多くの問題においては、観光地はまず観光客の観点に基づいて理解されるべきであり、そのことによってこそ地域として何をしうるのかという、より具体的かつ差別化された形での理解がもたらされることが指摘されている。

2 フローベース・アプローチ

我々は10年前に開始した学習プロセスを通じて、DMOの有効性のみならず、観光地やデスティネーション・マネジメントに関して広く認識されている概念の弱点へも疑問を持つようになり、観光の展開のあり方について、代替的かつ現実的な視点を構築するに至った。このことによって、我々は基本的な理論の基盤を刷新するのみならず、観光地における活動主体のための実践的なアプローチをも提供するものである。

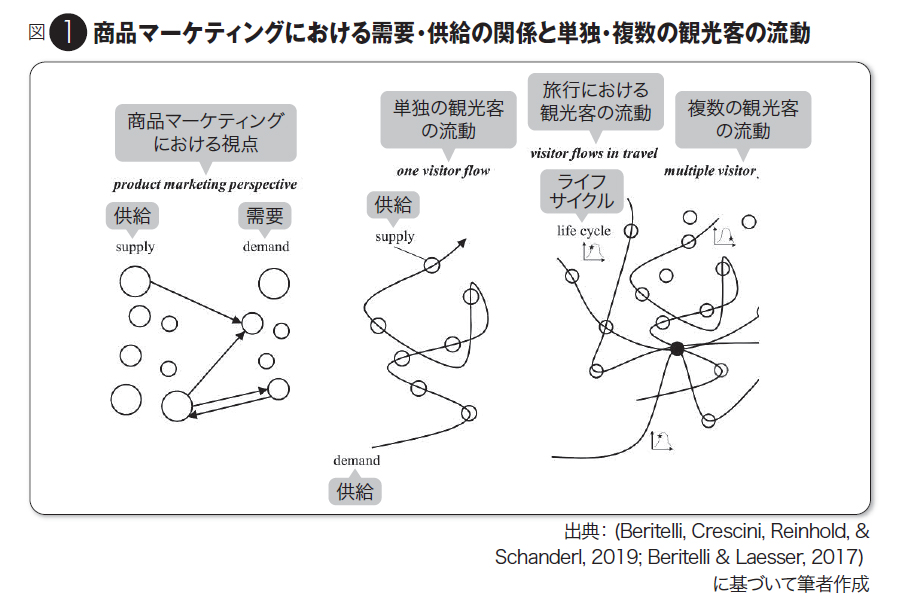

観光地は、いわゆる既製品ではなく、観光客が様々な地域資源を利用することが可能な空間である。このため、既往研究では「観光客との共同生産」、または観光客を「共同生産者」として扱う考え方が提示されている(Beritelli & Bieger, 2015; Kaspar, 1995; Maggi, 2014; Smith, 1994)。たとえ同じ人物が同じ場所を2回訪れたとしても、その度に異なる体験を「(共同)生産」することになる。また、記憶や思い出は新しい経験に応じて変化する。なぜならば、観光地は客観的あるいは実際的に見て、全ての消費者に同じ機能や便益を与える商品ではないからである。観光地のサプライヤーは、地域に多様で豊かな活力をもたらすため、観光客にその活動の場を提供することで、一貫した経験のため最適に構成された要素を提供する。言い換えれば、観光地は「生産過程」の起点となる観光客によって連結される地域資源や観光施設、観光サービス等の相互作用による壮大なエコシステムなのである。図1の左側は、従来の商品マーケティングの状況を表しており、様々な異なった種類の商品が供給側、セグメントやターゲットとなるグループが需要側に位置している。中間の図では、旅行は観光客(同じようなことを1日または半日の中で繰り返す人もいる)による流動的なプロセスであること、そして右の図では(中間の図のような)単独の流れだけでなく、ある地点で複数の観光客の流動(フロー)が同時に発生することを示している。

3 地図を活用した作業

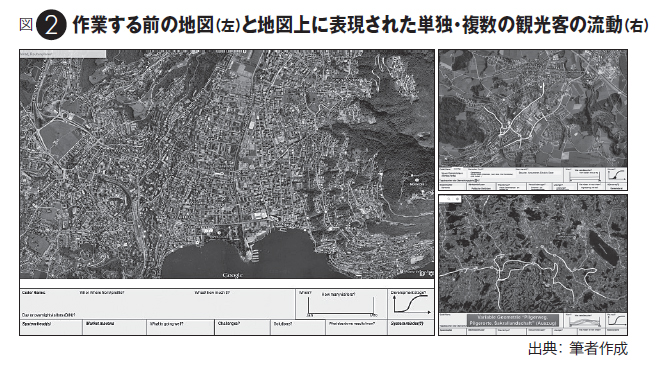

現在では、観光客の流動を再現するための様々な方法があり、最も洗練された方法としてはGPSを利用した追跡技術をベースにしたものがある(e.g.Kádár & Gede, 2013; Shoval, Schvimer, & Tamir, 2018)。一方で我々は、観光客と接する、もしくは観光客の様子を日常的に観察する手段がある現場のスタッフや地域住民に質問することによって、地域の観光資源や観光的な文脈を把握することができ、現在の観光客の流動や、さらには将来可能性のある観光客の流動予測について総体的に再構築することが可能であることを発見した。この方法では、正確性を高め、現場からのより具体的な情報を得るために、1つの地図ごとに1つの流動を直感的に描くことができる簡易なテンプレートを活用する(図2の左側を参照)。単独の流動だけでなく、特定の作業仮説(図2の右側を参照)に基づいて選択された複数の流動を重ね合わせて分析することにより、地域の関係者やそのパートナーに、共通認識や意思決定のための環境を提供することができる。

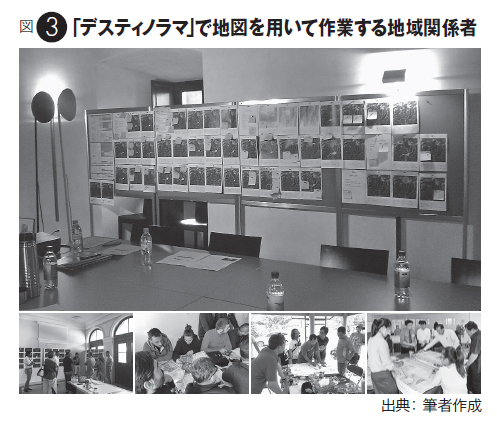

図3は、この方法を導入して世界中の様々な観光地で開催した会合の様子を示している。公的な空間に展示される単独の流動と地図は観光地の全ての関係者が閲覧することができ、観光地で何が起きているのか、という判別可能で詳細かつ具体的、さらには包括的な視点を提供することを可能にする。関係者たちも単独の(つまり各自が所属する)観光地だけについて議論するのではなく、それぞれの活動や協働のための方法や機会に関するより広い視野を持つようになる。我々は、この具体的であると同時に全体をも概観できる作業環境を「デスティノラマ(Destinorama)」と呼んでいる。

4 考察

この方法で作業を行うことは、様々な意味で全ての参加者にとって満足する結果を与えるものとなる。まず1点目に参加者は、観光は汎用的な形式やターゲットとするグループに限定されるものではなく、またいくつかの限られた観光関連企業だけが重要だというわけではないということを認識する。実際に数多くのニッチな活動が存在し、多くの観光地においては、ごく小規模な観光施設や企業こそが観光客の単独の流動に対して重要な役割を果たすとともに、観光客の行動の選択肢を豊かにすることにも貢献している。2点目に参加者は、観光客が目の当たりにする具体的な課題や問題について理解し、それに対する実践的な行動に向けたヒントを得ることができる。3点目に、地図を分析することによって、参加者は都市や土地利用計画、交通網、主要な観光施設、区域に関するより広範な課題を認識することができる。またそのことで誰がその事業や事項に取り組む責任があるのかを容易に特定することもできる。4点目に、DMOは地域で特定の活動を行う関係者を選択的に支援することで、DMO自身がより重要な役割を果たしうるということに気付くことになる。最後に、サプライヤー側から見た最も重要な要素は(商品の通常のマーケティングと同じように)、観光客が活動・交流する舞台、すなわち観光地の空間であり、DMOが差別化を図るべきはまさにこの点にあると考える。

ピエトロ・ベリテリ

1967年生まれ。ザンクト・ガレン大学(HSG)にて旅行や運輸分野の経営管理を学ぶ。グラウビュンデン高等専門学校観光学部講師(1993-1997年)、クール応用科学大学観光管理学部教授兼観光レジャー研究所所長(1998-2003年)を経て、2003年からザンクト・ガレン大学准教授およびシステム管理・公共ガバナンス研究所(IMP-HSG)副所長、観光運輸研究センター研究員。2004年からはザンクト・ガレン大学大学院の修士課程マーケティング・マネジメントプログラムの責任者も務める。スイスやオーストリア、イタリア、ドイツの他大学でも非常勤講師を奉職。観光関連企業や公的機関に対して観光地のマネジメントやマーケティング、観光政策、戦略マネジメントに関してアドバイスを行う他、複数の観光関連組織におけるボードメンバーとして観光産業にも積極的に関わっている。

1. Limitations of traditional Destination Management

Across the world, countries, regions, and communities aim to increase the value of tourism by better managing and marketing their territory. Destination Management has risen in importance in the last forty years or so, particularly because administrative bodies want to help visitors, tourism businesses, and locals in their efforts to improve on this diverse and diffuse phenomenon called travel. The result is often recognizable through organizations, often called DMOs (Destination Marketing or Management Organizations) that spend increasing amounts either for marketing communication and/ or for formulating strategies aimed at coordinating the tourism businesses, presenting comprehensive development plans. A critical analysis of what DMOs have produced until now, shows several misunderstandings, contradictions, or fallacies (for a comprehensive review see Beritelli, 2019; Beritelli, Bieger, & Laesser, 2014; Beritelli & Laesser, 2019; Beritelli, Reinhold, Laesser, & Bieger, 2015; Pike & Page, 2014):

•DMOs are responsible for a particular area defined by their adminisrative counterpart. However, visitors do not stop at municipal, regional or national borders when they take their trips.

•DMOs must define target groups and reach out to them with a meaningful marketing-mix. However, visitors pursue different activities, they seldom travel alone and present therefore heterogeneous groups, they sometimes visit friends and relatives, travel for business or come to a place for social obligations or because they have bound assets (e.g. a second home, a boat). Therefore, traditional market segmentation does not work in real travel.

•DMOs must market their area by attracting/ getting visitors but they cannot do so because they do not run major tourist businesses or attractions. If they try to sell tourist services for the businesses in the destination they do not reach satisfying sales volume.

•DMOs must manage tourism for the whole area but they do not have the resources and means to manage or coordinate every occurrence in tourism.

•Destinations must have a profile, specialize because they have to be managed like a product. However, visitors do many different things across the year in a given area. The greater the variety of activities and types of tourism the greater the likelihood of creating value for different businesses in different times of the year and for the long-term.

These and many other problems of Destination Management point to the fact that the destination is first to be understood from the visitors’ viewpoint and that this view opens the window to a more specific and differentiated understanding of what can be done from the supplier’s side.

2. The flow-based approach

In a learning process that started ten years ago and led us to question not only the effectiveness of DMOs but also the conceptual weaknesses of the commonly understood Destination and Destination Management, we have developed an alternative yet more realistic view of how tourism unfolds. By doing so, we have not only revisited the basic theoretical foundations but also offered a practical approach for actors in tourist places.

Since a tourist destination is not a prefabricated product but rather a space that makes various resources available to the visitor, we speak of tourist coproduction or as travelers as co-producers (Beritelli & Bieger, 2015; Kaspar, 1995; Maggi, 2014; Smith, 1994). Even if one visits the same place twice, she will (co) produce different experiences. Memories and associations change with every new experience. This is because a destination is not a product that objectively and factually provides the same functions and benefits to all consumers. In a tourist destination, providers provide at best combinable elements for a coherent experience, offering the playground for a most diverse and rich activation of peformances by the visitor. In other word, tourist desitnations are rich ecosystems of interplay between local resources, tourist attractions, services, etc. all connected by the visitor who plays the igniting trigger for the production process. Figure 1 illustrates at the left the traditional product marketing world with products of different kind and variation on the supply side and segments, target groups, on the demand side. In the middle and on the left we show that traveling is a fluid process performed by visitors ‒ some of them doing quite the same things in a day- or half-day sequence ‒ and where not only one (center) but multiple visitor flows take place, often simultaneously in a given area.

Figure 1: Supply-demand relationship in product marketing vs single and visitor flows in travel

Source:own illustration based on (Beritelli, Crescini, Reinhold, & Schanderl, 2019; Beritelli & Laesser, 2017)

3. Working with maps

Today, there are various methods to reconstruct flows. The most sophisticated ones build on GPS-based tracking techniques (e.g. Kádár & Gede, 2013; Shoval, Schvimer, & Tamir, 2018). We have found that asking front-line employees and locals who are in touch with visitors or have the means to observe them regularly, allows a collective reconstruction of current visitor flows and the projection of possible future visitor flows, given the existing resources and the travel context of the place. To increase preciseness and to gain more specific information from the field, we work with a simple template that allows intuitively drawing and describing one flow per map (see illustration in Figure2, left). Analyzing the single flows but also overlaying selected flows based on specific working hypotheses (see illustration in Figure 2, right), provides a common learning and deciding environment for the local actors and their partners.

Figure 2: Empty map (left) and single and multiple flows on a variable geometry (right)

Source: own illustrations

Figure 3 shows impressions of meetings in various destinations across the world, where we have implemented this approach. The displayed single flows and variable geometries in one public space, accessible to all actors of the destination allow a differentiated, detailed and specific, yet comprehensive view of all what happens in the destination. Actors argue less about one (‘their’) destination and have a wider perspective of options and opportunities for single actions or collaboration. This specific, yet at the same time panoramic working environment is called Destinorama.

Figure 3: Actors working with maps in the Destinorama

Source: own illustration.

4. Implications

Working with this approach is satisfying for all participants in several ways. First, they recognize that tourism is not limited to some generic forms or target groups and that not only some few tourist businesses are important. In fact, there are many niche activities, many areas where even little tourist attractions or businesses play an important role for the single flows but also contribute to the richness of the whole area’s portfolio. Second, they understand what specific challenges and problems are faced by the visitors and they have practical hints for actions. Third, by analyzing variable geometries, they recognize greater challenges referring to urban or land use planning, traffic, major attractions and zones. With that they can easily identify who is in charge for tackling these projects or initiatives. Fourth, DMOs find that they play a more important role by selectively supporting the actors for specific actions in the destination. In the end, the most important aspect at the supply side is ‒ just as in general marketing the product ‒ the stage upon which visitors performances take place and the visitors themselves communicate to their peers; in other words the destination’s space. We think that it is exactly here, where DMOs should make a difference.

Dr. Pietro Beritelli (*1967) has studied Business Administration at the University St. Gallen (HSG) with emphasis on travel and transport. 1993-1997 lecturer for Tourism at the Higher Vocational College of Graubünden, Samedan (CH). 1998-2003 Professor for Tourism Management and Director of the Institute for Tourism and Leisure studies, the University for Applied Sciences in Chur (CH). Since 2003 Associate Professor at the University of St. Gallen and Vice-Director at the Institute for Systemic Management and Public Governance (IMP-HSG), Research Centre for Tourism and Transport. Since 2004 Director of the Master Program in Marketing Management at the University of St. Gallen. Guest lecturer in other Universities in Switzerland, Austria, Italy and Germany. He advises tourist enterprises and public institutions in questions regarding destination management and marketing, tourism policy, and strategic management and is actively involved in the industry through mandates as board member of tourism organizations.

Bibliography

○Beritelli, P. (2019). Transferring concepts and tools from other fields to the tourist destination: A critical viewpoint focusing on the lifecycle concept. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2019.100384

○Beritelli, P., & Bieger, T. (2015). Herausforderungen des Innovationsmanagements in Netzwerken am Beispiel des Tourismus ‒ von der Theorie zur Praxis. Die Unternehmung, 69(3), 255-278.

○Beritelli, P., Bieger, T., & Laesser, C. (2014). The new frontiers of destination management ‒ Applying variable geometry as a function-based approach. Journal of Travel Research, 53(4), 403‒417.

○Beritelli, P., Crescini, G., Reinhold, S., & Schanderl, V. (2019). How Flow-Based Destination Management Blends Theory and Method for Practical Impact. In N. Kozak & M. Kozak (Eds.), Tourist Destination Management (pp. 289-310): Springer.

○Beritelli, P., & Laesser, C. (2017). The dynamics of destinations and tourism development. In D. R. Fesenmaier & Z. Xiang (Eds.), Design Science in Tourism (pp. 195-214): Springer.

○Beritelli, P., & Laesser, C. (2019). Why DMOs and Tourism Organizations Do not Really ‘Get/Attract Visitors’: Uncovering the Truth behind a Cargo Cult. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.9924428

○Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., Laesser, C., & Bieger, T. (2015). The St. Gallen Model for Destination Management. St. Gallen: IMP-HSG.

○Kádár, B., & Gede, M. (2013). Where do tourists go? Visualizing and analysing the spatial distribution of geotagged photography. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 48(2), 78-88.

○Kaspar, C. (1995). Management im Tourismus. Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt.

○Maggi, R. (2014).“Get there”, “Stay there”,“ Live there” – Household production of the tourist experience and its implications for destinations. Paper presented at the 2nd Biennial Forum “Advances in Destination Management”, June 10-13, 2014, St. Gallen (Switzerland).

○Pike, S., & Page, S. (2014). Destination Marketing Organizations and destination marketing: A narrative analysis of the literature. Tourism Management, 41, 202-227.

○Shoval, N., Schvimer, Y., & Tamir, M. (2018). Tracking technologies and urban analysis: Adding the emotional dimension. Cities, 72, 34-42.

○Smith, S. L. J. (1994). The tourism product. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 582-595.